VIDEO ARTICLE TRANSCRIPT

[Please note: This is a transcript of a video article. Some metadata elements may appear more than once in the document, in order to be properly read and accessed by automated systems. The transcript can be used as a placeholder or reference when it is not possible to embed the actual video, which can be found by following the DOI.]

[0:54]

SENTIENCE

SENTENCES

& SENTIMENT

SENSING DEEP-OCEAN

SEDIMENT THROUGH

ARTISTIC PRACTICE

video article by angela rawlings

[1:09]

‘Carbon footprint’ and ‘Anthropocene’ are new terms that conceptualise human and non-human interdependence. The Anthropocene is proposed as the epoch where human activity is inscribed in sediment globally (Crutzen and Stoermer, 2000; Finney and Edwards, 2016). Deep-ocean carbon sequestration is being considered to mitigate the climate crisis (Metz et al., 2005).

How might someone sense with marine and sediment ecosystems that will be impacted by increased carbon?

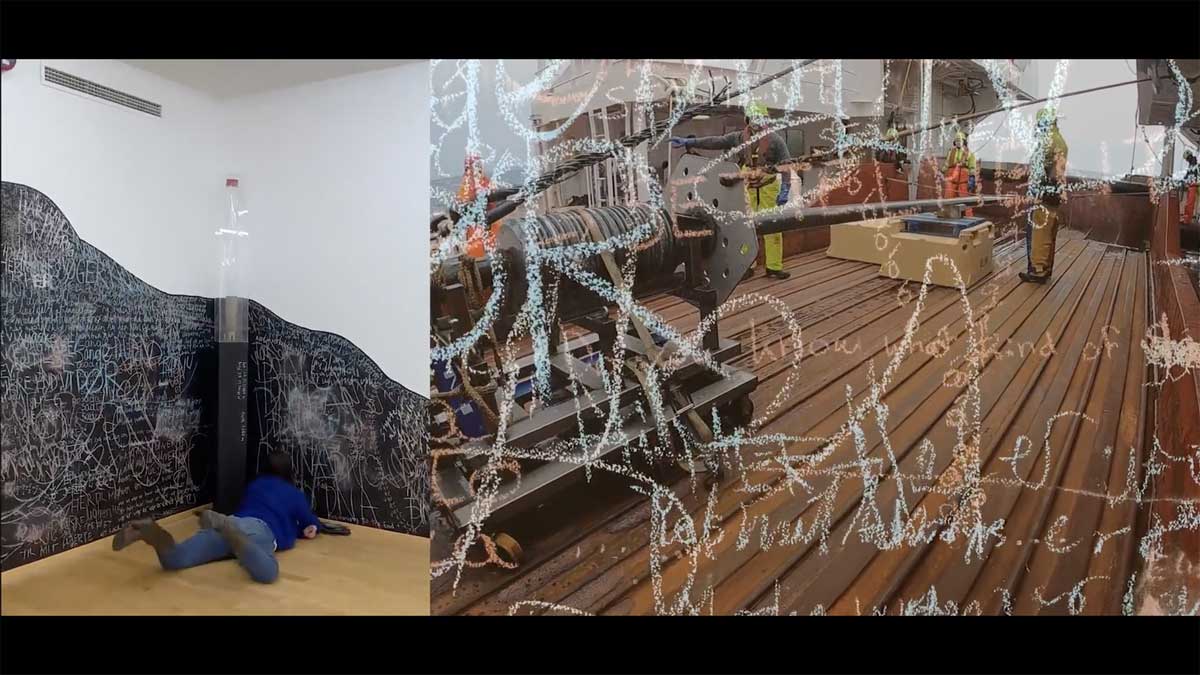

An artwork by postdoctoral researcher angela rawlings, kór (core) features a deep-ocean sediment core extracted between Greenland and Iceland at a depth of 1,682m during a June 2021 science research cruise. In Iceland’s Hafnarborg gallery (August to October 2021), the core was placed adjacent to a blackboard. Visitors were invited to write their sense-making with chalk.

This video article includes footage shot aboard the research vessel, documentation of the resulting artwork kór (core), interviews with gallery visitors, and an aria composed by José Luis Anderson using kór’s initial text as libretto.

KÓR

(CORE)

Installation for Hafnarborg group show

“Community of Sentient Beings”

28 August to 31 October 2021

Hafnarfjörður, Iceland

[2:15]

ANGELA RAWLINGS

Artist, Researcher

First and foremost, when I was on this research vessel this past June with the scientists and sailors, I started to kind of gather the vocabulary that was super present there. At a point when we took some of the sediment and put it under a microscope, the geophysicists who were present started to explain exactly what we could see in the microscope. So we could see drop stones, terrigenous muddy clay, silt, fine sand, etc., etc.

SEDIMENT COMPOSITION TERMS

drop stones, terrigenous muddy clay,

silt, fine sand, sideromelane, tachylyte,

alkalic ash, tholeiitic ash, pumice, quartz,

olivine, feldspar, obsidian, andesite,

rhyolite, coccoliths, calcium carbonate

And then the micropaleobotanist was then also talking a little bit through her interest in foraminifera and how she was always looking for that.

MARINE PALEOBOTANY TERMS

foraminifera, eukaryotic phytoplantkon

And this was a new word for me at the time, so I got really excited and I walked around the ship the whole time saying foraminifera, foraminifera… Beyond that, I was also really interested in the science-based imperatives that were coming through what would happen to a core once it was taken up. And so on this side, we see this collection of measure, measure, measure, observe, observe, observe—for different things like magnetic susceptibility or grain-size characteristics, oxygen isotopes.

Measure magnetic susceptibility.

Measure calcium carbonate content.

Measure oxygen isotopes.

Measure carbonate-free terrigenous fluxes.

Observe grain-size characteristics.

Observe modal composition.

Observe glass chemistry.

Lacasse, Christian, Haraldur Sigurdsson, Steven Carey, Martine Paterne, and François Guichard. 1996. ‘North Atlantic Deep-Sea Sedimentation of Late Quaternary Tephra from the Iceland Hotspot’. Marine Geology 129 (3): 207–35.

“Measure magnetic susceptibility measure

calcium carbonate content measure

oxygen isotopes measure

carbonate-free terrigenous fluxes

observe gran-size characteristics observe

modal composition observe glass

chemistry sound echo sound echo

echo echo”

excerpt from “area (aria)”

libretto: a rawlings

composer: José Luis Anderson

So I liked this combination of, you know, these random fairly obscure science terms and vocabulary that, you know, that doesn’t surface very often I guess, one could say, appearing within, at least, my periphery. I started to get a little bit of a sense of these gorgeous words that I don’t know. And then also with the instruction to do things that I have no idea how to do. I think this is really interesting, this kind of unknown or half-known. Once I got here, I was interested in taking three terms. Two I had learned while on the ship and then the third is a neologism—a made-up word.

GROUNDTRUTH

At the top, we have groundtruth. And I really love this as a term that was introduced to me by geophysicists in terms of—when sediment comes up, even before you do any of these data-capturing tasks, you can immediately get a sense through your own senses of that truth of the ground. And so, you know, it’s like, what does it smell like? What can you read in terms of your knowledge of the layering that happens? Groundtruthing!

BIOTURBATION

The other word I thought was super exciting is bioturbation. This word, of course, most of it is familiar through the term masturbation. We just change the mas- to bio-. And bioturbation means the stirring up or the mixing up of ground or sediment by living organisms. So this was another, like, “OH! COOL! Okay.” And this is what we are doing as humans when we are going down and piercing the sea floor. And then also what’s happening with the benthic community, the worms and whatnot that live down in the sea floor in the top layers.

SEDIMENTALITY

And then sedimentality—I was just thinking quite a bit about the affective. Sentimentality… Sediment… What’s the sentimental within the sediment or how does one form a sentimental relationship with sediment?

Beyond that (this is really long-winded!), I was then thinking it makes me really itchy to have English as the dominant language—the language that’s at the top. Of course, this was the language that was common and being used within the research. But we are in Iceland and I started to think, okay, let’s bring in some of the Icelandic words or terms for these things. So the next layer that kind of comes on is some Icelandic translations of these.

SEDIMENT COMPOSITION TERMS

IN ICELANDIC

dropasteinar, drullu leir, fínn sandur,

basísk aska, vikur, kvars, hrafntinna,

kalkhreistri, kalsíumkarbónat

And then beyond that, and what will start to populate the rest of this, are words that I’ve invited people who come and engage with the sea floor to add—their words in many languages and also neologisms.

[6:55]

ON GESTURES

LOCATIONS

& TEMPORALITIES

HALLA STEINUNN STEFÁNSDÓTTIR

Composer

So I wrote the word ‘far’ and ‘far’ can both be an imprint or a vessel, or you can actually get a ‘far’. You can actually be brought by somebody, for example, in a car. But yeah, it has both this… I think it has… It calls out to this piece in that we have a very strong imprint here but it can also invite you on an affective journey. It’s a vessel.

[7:50]

STEINAR BRAGI

Writer

The word is ‘aðfall’. So I thought of the sea floor and my family has a summerhouse in Mýrar, like since I was a kid. You could go to the coast by a place called Keldan where the sea—like, what’s the English word for it?—when the sea gets sucked out because of the moon…?

Then slowly the sea floor becomes like… The sea completely disappears, like, for a couple of hours where you can cross the sea floor to enter an island. And all the while you’re staying on the island, you’re thinking about ‘aðfall’. Everything you see on this island is ‘aðfall’ because you have a specific amount of time to stay there before the ‘aðfall’ happens and the sea closes you off from the mainland.

[9:15]

ANNIE CHARLAND THIBODEAU

Artist

I chose the word ‘foret’ because this is the tool that you would use when you’re piercing a hole to extract the core. But it also is very close to the word forest; it’s a French word—forêt. And if you were to add an accent on top of the ‘e’, then it can also play with the word forest.

[9:40]

EWA MARCINEK

Writer

So my word is ‘dno’ which in Polish means the bottom, like a sea bottom or the bottom of your cup or emotional bottom—like, be at the bottom. Być na dnie. But I love it because ‘dno’, you spell it ‘d’, ‘n’, ‘o’. Looks almost ‘DNA’. So it connects us to some roots or the beginning of everything. And this is where I put ‘dno’: at the very bottom.

[10:23]

JORDI CORTES

Humanitarian Aid Worker

I chose ‘beginning to the end’ because this piece really made me think about what it was meant to be at the bottom of the sea or the sea floor. And I guess it’s that, you know, that’s when you’re on a ship or on a submarine or when you’re swimming and you reach that really low part with the sea floor. We tend to think that that’s the end. You’ve reached, you know, you’ve hit rock bottom. There’s nothing else beyond us. Whereas the sea floor, everything starts, you know—where life grows, where life starts. And also beneath that sea floor level, there are also layers from the earth. So it’s never the end—that, you know, reaching the earth, the sea floor. That’s what came to mind when I was thinking about this.

ON COMPOSITION

DIRECTION

& RELATIONALITY

[11:50]

ANNIE CHARLAND THIBODEAU

Artist

And the way that I engage also with this piece and with the core is that the way it is offered to the audience here is also, in a way, some kind of mediation and offering a close contact with something that most of us can’t witness otherwise.

[12:15]

HALLA STEINUNN STEFÁNSDÓTTIR

Composer

It’s coming from talking about different types of signs. So this is sort of coming from a musical diminuendo, something that is diminishing and it just appeared there. It’s in there, in the silt. There is a sort of a diminuendo inside there, although I also do see a dog in a pen. But it’s like—it sort of falls within there and then it dissolves into silt which falls within the tradition of graphic scores—so very open to interpretation and then I continued looking at this and drew out of that a sort of another graphic fragment that can be used, I mean, that can of course stand as something sort of spatial. But I would use it as a graphic score sort of and it’s coming from there, from the tip of the diminuendo. So it’s a pattern or something that appears. And of course, this is more of an impression; it’s not accurate, but a chalk impression.

[14:00]

JOSÉ LUIS ANDERSON

Composer

I chose to write ‘saga’, the word in Icelandic for ´story’, because that’s what I thought when I was looking at the core because it’s very old. So it somehow tells the story of the world or the planet or many other things. And then I chose to write it here because of the word ‘echo’ and ‘sound echo’… because somehow a saga… Well, what is an echo of a sound but a refraction of sound which also tells a story. Sound tells a story and then an echo is just the story of a sound that was produced, that reflects that. So. Yeah.

[14:50]

SOUND

ECHO

Anderson’s aria was composed in tandem with the development and installation of the artwork kór (core). Text inscribed through chalk on the exhibition walls becomes the libretto of Anderson’s aria. Both Anderson and rawlings embody text through extended vocal technique.

Echo-sounding screenshot captured by geophysicist Paul Knutz (Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland). Blue rectangles indicate sediment-coring sites.

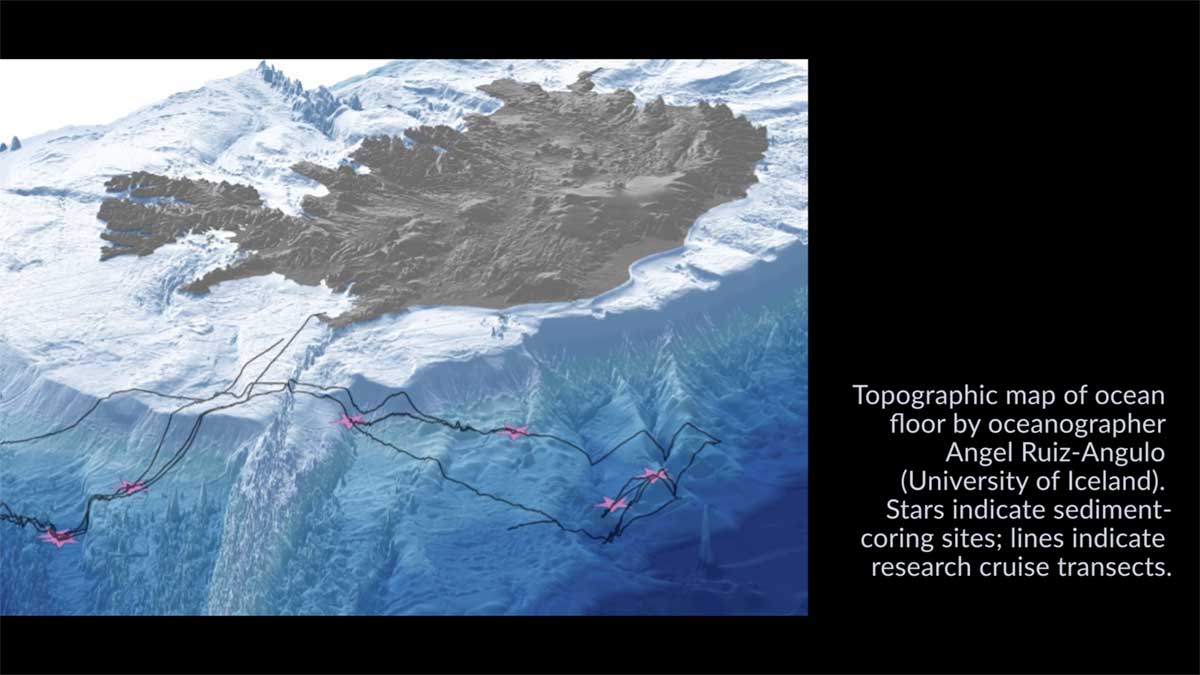

Topographic map of ocean floor by oceanographer Angel Ruiz-Angulo (University of Iceland). Stars indicate sediment-coring sites; lines indicate research cruise transects.

ON CIRCULARITY

AFFECT

& SENSING

[17:03]

EWA MARCINEK

Writer

Coming from the first few words, I realised that there is this ‘sad’ that is very common in Polish language to build around, and it means something about sitting. And then I was wondering, what is this ‘o’ here as a prefix? And I learned by googling that actually one of the uses of the prefix ‘o’ is about down—so this idea of like ‘osad’, this sediment going down. And I was thinking about—because there’s so much about the bottom and there is the sad dolphin here—so I was thinking about being ‘sad’, why ‘sad’ is being down and why hope and help is up. So ‘are you down’ means ‘are you sad’. But it’s also a place to be. So is our sadness located somewhere there? And then we played with Icelandic—‘ertu niðri?’ which at least we know it works for the location. But does it work for the mood?

And then I offered the Polish mix of location—czy jesteś na dole?—which, dół means a hole in the ground or the direction ‘down’. But to be sad is ‘mam doła’; I have a hole in the ground. So this is a mix. Are you in the hole in the ground or—meaning are you sad or are you located below?

[18:55]

CHALK is a sedimentary carbonate rock—

limestone formed through the compression

of plankton that have fallen to the ocean

floor. The familiar chalk of childhood meets

its in-process source: deep-sea sediment in

the constant practice of becoming.

[19:13]

MICHAEL RICHARDT

Performance Artist

Du har noget / You have something

Du hart il mig / You have for me

Du / You

Her / Here

Rigtig meget her og nu / Really a lot of here and now

Ogsaa meget droemmer / Also a lot of dreaming

Droemmer / Dreaming

[20:58]

[angela rawlings]

I think that’s the last thing I’m going to write. In Icelandic, I’m writing ‘var hér’, which means ‘was here’, and thinking about how especially with graffiti tagging it’s common to write ‘so-and-so was here’… ‘I was here’… ‘angela was here’, etc…. and so not giving a proper name to whoever or whatever was here, I’ve just been writing ‘was here’, ‘was here’ but in Icelandic—‘var hér’, ‘var hér’, ‘var hér’ everywhere, also thinking about how while I’m doing this process of writing ‘var hér’, I’m thinking quite a bit about how humans have inscribed themselves throughout planetary sediment since 1945 with the detonation of the first nuclear bomb. Now we see presence of human activity acting as a geologic force. So it’s like humans are writing ‘human was here’, ‘human was here’, ‘fólk var hér’, ‘fólk var hér’ into the sediment, into a deep-sea floor.

[23:22]

SENTIENCE,

SENTENCES

& SENDIMENT

Video article by

angela rawlings

Video footage by

a rawlings, Michael Richardt,

Annie Charland Thibodeau

Audio by

José Luis Anderson

& a rawlings

ÞAKKA YKKUR ÖLLUM

For “kor (core),” rawlings acknowledges the support of RANNÍS, Carlsbergfondet, and Research Centre on Ocean, Climate, and Society. Gratitude to all interviewed, to sailors and researchers depicted in footage, and to Hafnarborg and curators for bringing this work to audience.

KEYWORDS

deep time, geochronology, Anthropocene, geopoetics, carbon sequestration, interdisciplinary, artistic practice-as-research, embodiment, attunement, slow installation, sediment, deep ocean

ABSTRACT

At this moment of climate crisis, deep-ocean carbon sequestration has been proposed as a strategy to curtail greenhouse gas emissions. The video article Sentience, Sentences, & Sentiment: Sensing Deep-Ocean Sediment through Artistic Practice explores ecological attunement and the role of language in perceiving the more-than-human—specifically the deep-ocean ecosystems facing potential carbon sequestration, ocean acidification, global heating, and eutrophication. The article unfolds an artist’s account of process for kór (core). An interdisciplinary artwork and slow installation, kór (core) features a deep-ocean sediment core extracted between Greenland and Iceland at a depth of 1,682m during a June 2021 science research cruise. In Icelandic, kór means choir or chorus; it is pronounced similarly to the English-language core. The article features video aboard the research vessel, the acquisition of the core, conceptual documentation of the resulting artwork kór (core), participant interviews, soundscape recordings, and an aria composed through the installation.

kór (core) performs a slow installation as a point of activation, where community members contribute to, think with, and create in the context of considering the sentient being-ness of sediment. On a chalkboard, community members mark their reactions to and within the presence of deep-ocean water and sediment. This article shows multilingual sense-making (English, Icelandic, Polish, Danish, Spanish) and the sensorial materialities of bodies (human, cetacean, water, etc.) in the contexts of marine-terrestrial biospheres impacted by the climate crisis. The video aims to elucidate a creative investigation into an expanded notion of relations—crucial for collaborative survivorship in our multi-entity worldings.

BIO

angela rawlings is an interdisciplinary artist whose books include Sound of Mull (Laboratory for Aesthetics and Ecology, 2019), Wide slumber for lepidopterists (Coach House Books, 2006), o w n (CUE BOOKS, 2015), and si tu (MaMa, 2017). rawlings holds a PhD from the University of Glasgow where she researched how to perform geochronology in the Anthropocene.

REFERENCES

Crutzen, P.J. and Stoermer, E.F. (2000) ‘The Anthropocene’, Global Change Newsletter, 41, pp. 17–18.

Finney, S.C. and Edwards, L.E. (2016) ‘The “Anthropocene” epoch: Scientific decision or political statement?’, GSA Today, 26(3), pp. 4–10. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1130/GSATG270A.1.

Lacasse, C. et al. (1996) ‘North Atlantic deep-sea sedimentation of Late Quaternary tephra from the Iceland hotspot’, Marine Geology, 129(3), pp. 207–235. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/0025-3227(96)83346-9.

Metz, B. et al. (2005) Carbon Dioxide Capture and Storage. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Available at: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/carbon-dioxide-capture-and-storage/ (Accessed: 7 August 2021).

Richardson, K. (2021) ‘Cruise Report ROCS June 2021’.

ROCS research cruise (2021). University of Copenhagen. Available at: https://rocs.ku.dk/news/2021/rocs_research_cruise_2021/ (Accessed: 10 July 2022).

Ruiz Angulo, A. (2021) ‘Just after 9 days of my new position at the University of Iceland, I joined the #ROCS_Centre team, sailing over the Reykjanes ridge; interesting cores and upper turbulence #RSI_Turbulence.. also heavy waves!!’, Twitter. Available at: https://twitter.com/angelruizangulo/status/1405265841084534787 (Accessed: 10 July 2022).

References

Crutzen, P.J. and Stoermer, E.F. (2000) ‘The Anthropocene’, Global Change Newsletter, 41, pp. 17–18.

Finney, S.C. and Edwards, L.E. (2016) ‘The “Anthropocene” epoch: Scientific decision or political statement?’, GSA Today, 26(3), pp. 4–10. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1130/GSATG270A.1.

Lacasse, C. et al. (1996) ‘North Atlantic deep-sea sedimentation of Late Quaternary tephra from the Iceland hotspot’, Marine Geology, 129(3), pp. 207–235. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1016/0025-3227(96)83346-9.

Metz, B. et al. (2005) Carbon Dioxide Capture and Storage. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Available at: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/carbon-dioxide-capture-and-storage/ (Accessed: 7 August 2021).

Richardson, K. (2021) ‘Cruise Report ROCS June 2021’.

ROCS research cruise (2021). University of Copenhagen. Available at: https://rocs.ku.dk/news/2021/rocs_research_cruise_2021/ (Accessed: 10 July 2022).

Ruiz Angulo, A. (2021) ‘Just after 9 days of my new position at the University of Iceland, I joined the #ROCS_Centre team, sailing over the Reykjanes ridge; interesting cores and upper turbulence #RSI_Turbulence.. also heavy waves!!’, Twitter. Available at: https://twitter.com/angelruizangulo/status/1405265841084534787 (Accessed: 10 July 2022).