VIDEO ARTICLE TRANSCRIPT

[Note: This is a transcript of a video article. Onscreen text appears left justified, while spoken words are indented. Individual elements from the transcript, such as metadata and reference lists, may appear more than once in the document, in order to be properly read and accessed by automated systems. The transcript can be used as a placeholder or reference when it is not possible to embed the actual video, which can be found by following the DOI.]

[00:10]

Sartorial Sessions

Introduction

The research approach

Zepp (Watercatcher)

Zepp (Crouch)

Zepp (Wrap)

Bruno (Sand)

Bruno (Sweat)

Joy (Material Sensing)

Joy (Expressive Gesture)

Narmine (Expressive Gesture)

This video article discusses and presents research that stems from an iterative process encompassing the design of garments and their use in “sartorial sessions.” Sartorial sessions are participatory research activities where individuals try on, wear and explore purpose-designed fashion garments in combination with sensory-tactile materials that include water, sand, and seeds. The sessions generated bodily responses such as movements, behaviours, and interactions which were documented using digital video and then subject to close examination and exploration.

[00:50]

Introduction

The kinds of movements that are the subject of the videos would pass unnoticed within most of our face-to-face interactions, not only because such movements are ephemeral and transitory, but also because as largely mundane movements they don’t carry the legible meanings we are conditioned to see. They are the ordinary micro-bodily adjustments bodies are always making: a small movement of the hand to smooth a garment, or to emphasize expression; a scratch of our face; or a small step to vary posture or orientation; or any of the multitude of movement variations human beings enact.

It is important to note these videos are not straight-forward documentation. The project involved the digital capture, then manipulation of body garments interactions that emerged in the sartorial sessions. This identification of instances of body and garment interaction, followed by manipulation and elaboration of those movements, results in an extended and rhythmic sequence of corporeal movement. This process extends movements, of what were initially small, phases of movement or gestures, often only a single instance spanning a few seconds, to a much longer and significant sequence. In doing this I transform what was normally mundane and unnoticed into a visible and significant thematic concern.

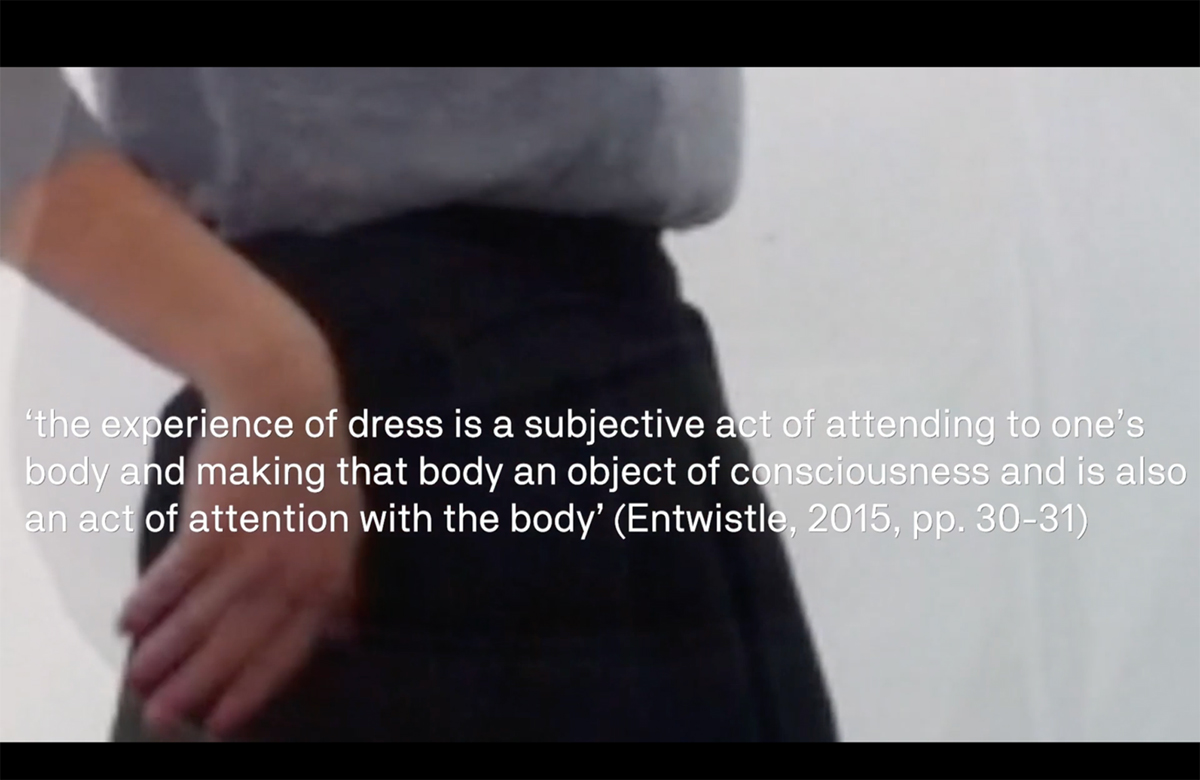

Historically the body in fashion has been examined semiotically, understood as an image, sign or symbol. However, this project sought to examine the body and the garment as garment as an unfolding flow of embodied movement or vitality.

The research utilised digital video’s capacity to excavate aspects of corporeal life normally unavailable to our natural perception. The critical orientation is located within a lineage of research on embodiment in fashion that calls for recognition of the sensuous, affective and experiential aspects of being dressed.

‘the experience of dress is a subjective act of attending to one’s body and making that body an object of consciousness and is also an act of attention with the body (Entwistle, 2015, pp. 30–31)

(Ruggerone, 2017, Entwistle, 2015, Negrin, 2016)

These important contributions have argued for frameworks for embodiment research in fashion and serve as an important methodological scaffold for empirical work on the body and its relationship with clothing.

[03:05]

The Research Approach

The research involved participatory events: the design of a small-range of purpose-designed fashion garments that were used in conjunction with sensory-tactile materials that were used as sensory prompts or provocations. The aim of the sensory provocations was to provoke and elicit sensory experiences from participants which could be captured, documented, and analysed.

The purpose designed garments encompassed two small ranges. One a masculine informed set of garments, consisting of two identical designs of trousers and coat, in black, blue, and a sand colour linen fabric. The second included feminine styled series of garments, included a skirt, dress and top all in black linen. Five individuals participated in the sartorial sessions which involved the trying on and exploration and wearing of these garments. These were invited from my creative and professional networks, and all participants had interest in fashion and self-styling.

The garments were designed on one level to conform to contemporary design aesthetics, but also to coordinate as a range to offer variety of sartorial possibilities. Different garments in the range relate to different parts and zones of the body. Some garments are in direct contact with the body, such as a dress, which was fitted around the hips, while the blouse section was loose at the top, while others produce more space around the body. For example, the pleated skirt, trousers and coat produce a sense of space internal to the garment around the body that enables ease of movement and increased scope for interaction and play. Participants were free to select pieces they wished to wear, often teaming them with items from their own wardrobe.

In the videos that follow each sequence is focused on the use of a sensory material. This includes water, denoted by blue garments, sand indexed to beige coloured garments, while black seeds are used within black garments. The seeds were sewn inside channels and placed in the pockets of the garments. Only the water is a visible in the videos. The process was iterative and took place over a 12-month period. The primary focus of these sessions was to create “live complexity” in the form of movement, action and behaviour which could be digitally captured and subsequently examined and manipulated and then reflectred upon.

[05:53]

Zepp (Watercatcher)

On screen you can see Zepp (Watercatcher). He’s wearing a blue outfit. In this sequence water was used as the sensory provocation. Flowing water was used to produce a simple narrative of corporeal and material transformation of dry to wet. As the blue fabric darkens by the water, his bodily movements correlate with this sensory-material encounter. The specific focus of this video is this process, but also the movements of his hands. By orienting the backs of the hands to flowing water, he appears to shift from an active mode, where he catches water in the cupped hands, to an acquiescent relationship to the water. This is noted as he rotates his hands to the back, he also orients his body towards the water, such that it flows directly onto his body, falling onto his shoulders and hair.

[06:50]

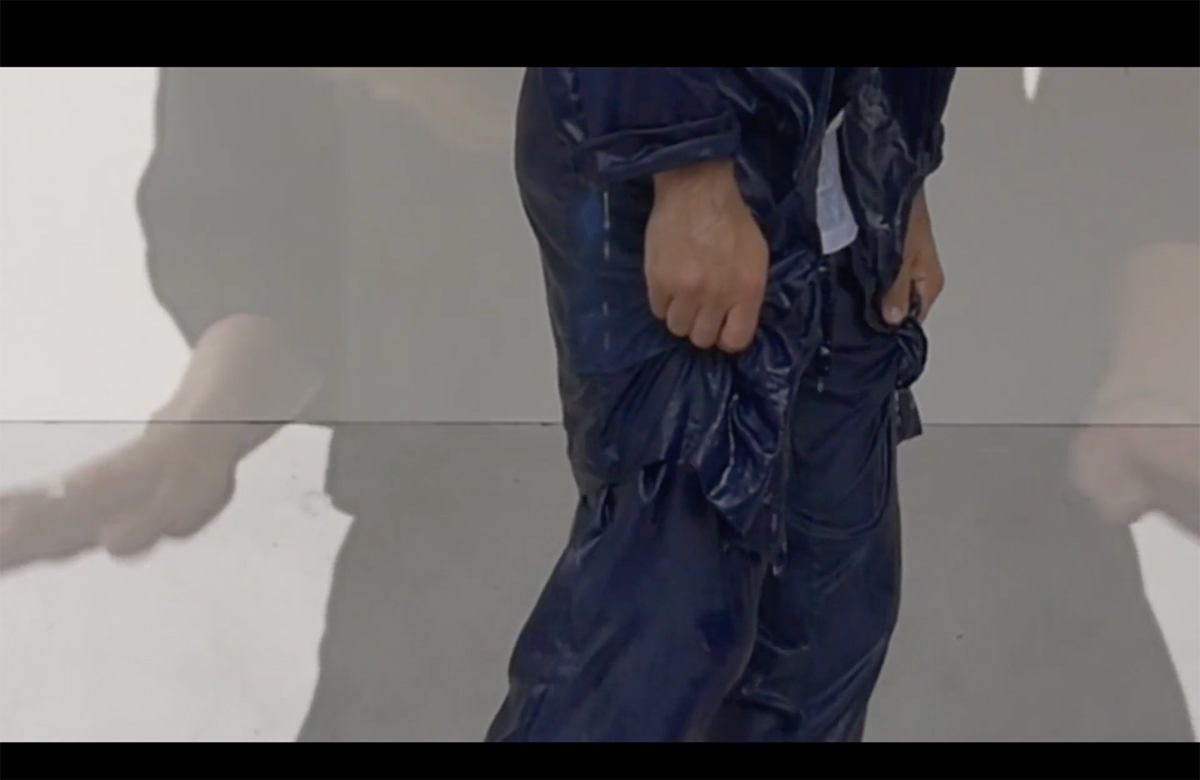

Zepp (Crouch)

The figure on screen is now completely saturated. The garments cling to his body, limiting his movement. Wet hair falls, obscuring the face. His body movement traces a path up and down; the full extension is constrained by the wet garments that stick them. He bends at the knee and at the same time his hands manipulate and arrange fabric that bunches at the front and side of the coat pocket. As he rises, he hitches up the trousers to move his body into a crouching position. The wet garments cling to the body and a “hitching” action releases the fabric and frees the body’s movement.

The sequence reveals the subtle complexities of what is normally considered a mundane movement. As anyone who has worn trousers would somatically understand, the need to hitch up a small amount of fabric onto your thighs and hips, so when sitting down or crouching, the change to the body’s position can be accommodated. This everyday and relatively commonplace movement of hitching trousers up brings into view the way in which the body’s movements and the garments are coordinated and set in a relation of mutual effect.

The movements that emerged as significant and that are the focus of this article in the micro-corporeal, incremental, and improvisational adaptions our bodies are always enacting.

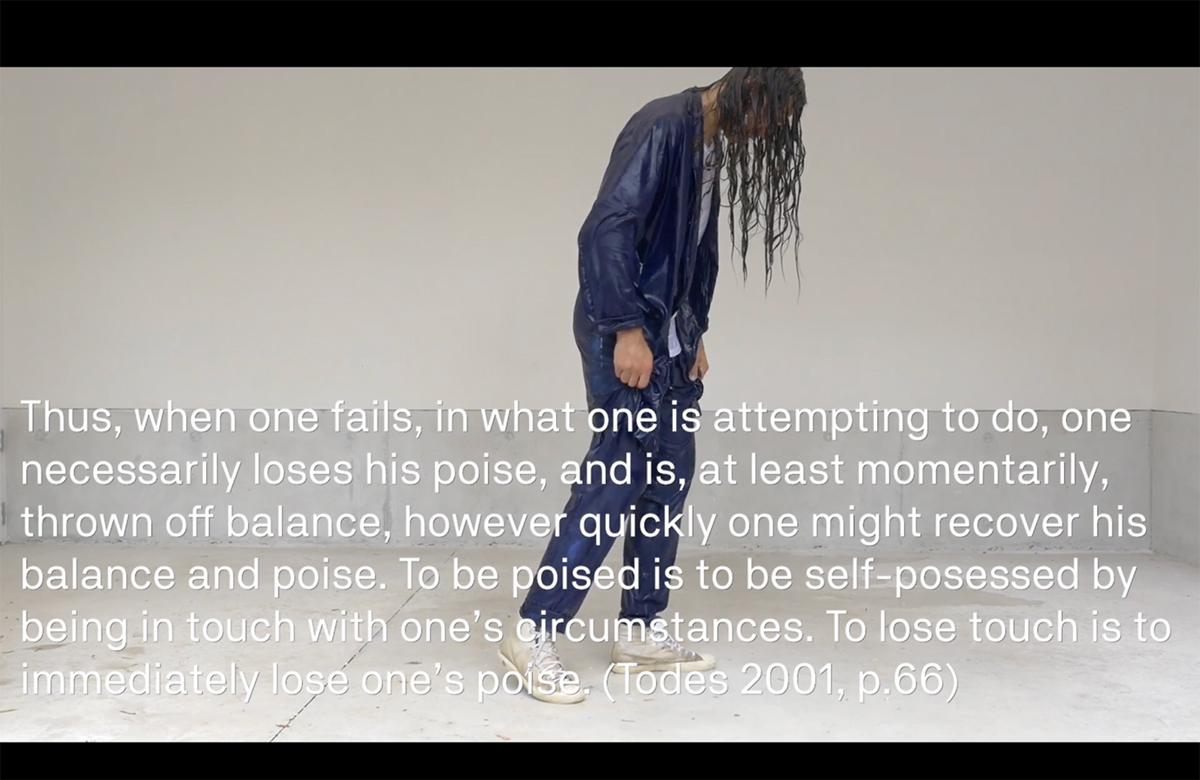

Samuel Todes (2001)

Samuel Todes referred to the lived condition for human beings to find and maintain a felt sense of ease or balance in our interactions with others and things around us as “poise.”

Thus, when one fails, in what he is attempting to do, one necessarily loses his poise, and is, at least momentarily, thrown off balance, however quickly one might recover his balance and poise. To be poised is to be self-possessed by being in touch with one’s circumstances. To lose touch is immediately to lose one’s poise. (Todes 2001, p.66)

These movements observed in the sartorial sessions can be understood as the body’s way of seeking a felt sense of ease or balance or “fit.” This sense of poise was not obtained immediately but resulted from coordinated movements, each calibrated as a more refined response to the one that precedes it. This sense of balance or fit is not a static point, but rather a forward-going series of adaptive movements where the body and garment respond to each other in a mutual kind of becoming or exchange.

[08:58]

These forms of adaption might also be physiological and related to our environment, in terms of comfort, which may be in terms of temperature or our awareness of what is happening around us.

Zepp (Wrap)

Here the figure’s shoulders and torso rise and expand over a few seconds, and it becomes apparent a deep breath is drawn, then exhaled, signalled by a drop of the shoulders. This effect is known as the dive reflex or “diving bradycardia” and involves a breath-holding reflex and slowing of the heart rate. It is typical of all mammals and is said to be a reflex response believed to conserve oxygen during immersion in water. This response, as well as the wrapping on the garment around his body to preserve body warmth, or the movement to smoot wet hair away from the face — not as a preening gesture, but rather simply to enable one to see — reveal our integration with our environment. There is something basic about these series of corporeal movements and their emergence signifies modalities of movement that are aligned with adaptation and changes to environmental conditions. In these movements the body emerges in terms of its vulnerability and an adaptive relationship to the broader physical environment.

[10:37]

Bruno (Sand)

While adaptive movements emerged during the research sessions, there were also movements that are closely associated with somatic experience that are interesting given they lack legible meanings, however they register emphatically in strong physical movement. Bruno is scratching and rubbing his neck, shaking his hair and body, with sharp jerky convulsive movements. These kinds of movements, such as the scratch or rub, can be delineated from the more legible or clearly articulated movements associated with practical work or communicative gestures. Their mundane origins and fragmentary nature means that a scratch or a rub rarely becomes the subject of explicit analysis. These smaller dynamic components of movement resist articulation.

‘vitality affects’ which are according to Stern are: ‘not direct cognitions.. they have no goal state and no specific means. They fall in between the cracks. They are the felt experience of force – in movement – with a temporal contour, and a sense of aliveness, of going somewhere. They do not belong to any particular content. They are more form than content. They concern the “How”, the manner the style, not the “What” or the “Why”

These kinds of movement though do draw attention, not to movement per se, but how sartorial movements are associated with bodily sensations and particular ways of experiencing our bodies, which themselves reflect the dynamic and fluid nature of movement and experience in general.

[11:30]

Bruno (Sweat)

Towards the end of Bruno’s session, two irregular patches of sweat started to form on his back, no doubt generated by the air temperature and the intensity and exertion of his physical movements. These markings offered a unique phenomenon in the context of this research. They pointed towards continuous and ongoing internal bodily processes that are distinct from the body’s more visible and often intentional actions and movements that are available to others. The markings indicated those silent physiological processes that reveal themselves infrequently and evoke Drew Leder’s notion of the “recessive body.”

These are movements stem from our biological nature and deep integration with our environment and suggest non-cultural anomalies and bodily processes are also a part of our sartorial life.

[12:28]

Joy (Material Sensing)

The movements of Joy’s hands are in the front area of the skirt. She does not address the grey marl top, which is hers, or any other part of her body, but are drawn to the front surface of skirt. She interacts with this area as a membrane of some kind, as a gently tensioned tissue stretched across two points. Her first action involved pinching fabric between the fingers and drawing it out towards the sides of her body. This created a tensioned skin or membrane, while the second set of movements is directed towards an exploration of the surface, as if playing the surface of a small drum. Her finger pads gently tap the surface, although not to produce sound, but to explore its surface, to examine or test the limits of the tension with tiny applications of pressure. This movement also suggested the tactile sense was oriented towards the body beneath the textile. Joy’s touch is via the fingertips and pads and explored the tensioned surface of the fabric. This was firstly through tensioning the fabric itself, and then using the finger pads to explore its skirt surface as a membrane. These observations are based on the fact that no mirror is available here to observe oneself and it is arguable this modality of touching is in fact a way to gather information about the status of the body beneath the garments.

[13:56]

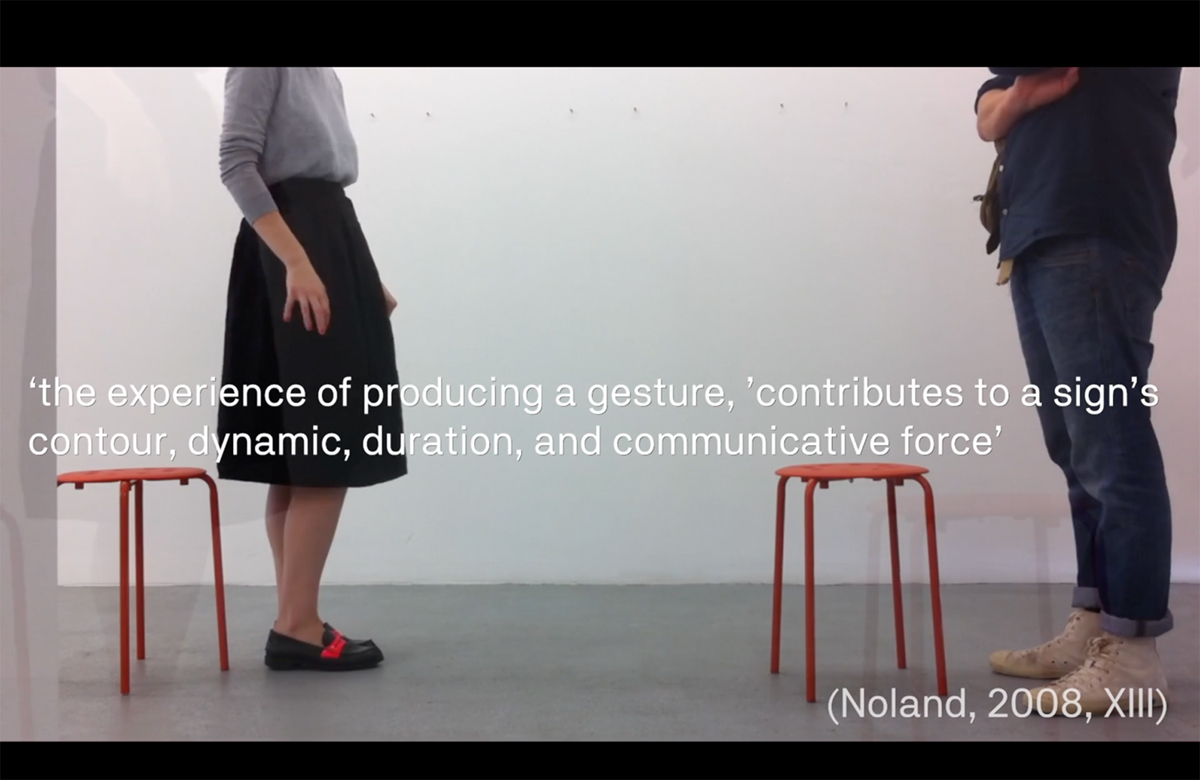

Joy (Expressive Gesture)

In this session, Joy made some gestures while at the same time explaining her sartorial experiences, her likes and dislikes. However, these same movements which you can see on screen, when detached from the semantic content of her speech, can be understood as signifying and reflexively recalling what are in fact privately experienced somatic sensations and experiences of being dressed. There exists a complex relationship between the semantic content of a gesture and its lived experience. While those gestures are largely ambiguous and under-determined, they nonetheless highlight the continuities between the physical enactment of signifying those gestures and how the visceral and kinaesthetic experience of enacting them informs the actual shape of those gestures.

‘the experience of producing a gesture, ‘contributes to a sign’s contour, dynamic, duration, and communicative force’

In this sense it is the shape, contour and expression of those movements that can convey something of what it feels like to be dressed.

[14:57]

Narmine (Expressive Gesture)

Narmine moves her hands in and out of her pockets. They emerge in a graceful winglike motion, then return to the pocket. This movement complicates the notion that sartorial expression is produced for the visual consumption of another. It can be said public performances of dressed bodies are an important aspect of fashion, understood as a cultural practice. This aspect of sartorial life is pleasurable through its participation in a shared social and cultural community, as well as the visual pleasure of looking and being looked at.

However, Narmine’s movements suggest there may be ways of being comported in public space that does not orient the body towards others. Within those unusual yet graceful movements, I identify a somatically experienced sartorial pleasure in being-dressed. For example, there are moments when I have experienced the sensation of sartorial movement in the experience of walking, a reverie, and one is happy in one’s skin.

Narmine’s movement is somewhat resonant of Baudelaire’s flâneur. Born of nineteenth-century Paris, the flâneur was a well-dressed gentleman who walked without haste and was led by the visual lures of an incipient modern metropolis.

Ambling through the newly built shopping arcades, public parks, and squares, the flâneur was distinguished by an excessively leisurely pace and a complete abandonment to the aesthetic pleasures of urban life.

The flâneur would be pursuing no end nor making his way to any particular destination but would be completely absorbed in a kind of reverie. According to Baudelaire, the flâneur could quite paradoxically lose and find himself in the faces of passers-by, their fashionable dress, in building facades and advertisements, and the new and seductively displayed goods found in the shop windows.

The fluency of the movement expressed by Narmine indicate a similar mode of absorption, but not in the visual displays around her, as there was little for her to observe in the plain unadorned room in which the sartorial sessions took place. But rather in the self-fulfillment of poise, when one achieves a felt sense of comfort, of poise, in what one is wearing. It is not important to the flâneur if he is the subject of the gaze of others or not. His pleasure derives from aesthetic absorption of the urban environment around him, not from the availability of his body for others.

[17:43]

Conclusion

My encounter as researcher, discussed in this video article, encompassed activities of reading, writing, theoretical engagement, and practical activities, aspects of which can be seen in these videos. These diverse encounters and what they mean are informed by the disciplinary orientation of my own emplacement in fashion as both a maker and wearer of fashion. Thus, the framing of this study, the research design, and the encounter with the research material generated by the methodology are inextricably linked to the disciplinary-shaped ways I perceive, experience, and understand the corporeal experiences of my own body, as my body is involved in fashion, as well as the bodies of others that do the same. In this sense I reflexively and self-consciously utilize these disciplinary ways of knowing to draw out the significance of distinctive movements enacted by bodies that participated in this research, against a background of my own strongly felt, embodied historical experiences in fashion, and to share those moments with others.

[18:55]

Reference list

Benjamin, W. 1999. The arcades project. Translated by Howard Eiland and Kevin McLaughlin. Cambridge, Mass.; London: Belknap Press.

Entwistle, J. 2015. The Fashioned Body; Fashion, Dress and Modern Social Theory. 2nd ed. Cambridge, UK & Malden, USA: Polity.

Leder, D. 1990. The Absent Body. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Noland, C. 2008. “Introduction.” In Migrations of Gesture. Minneapolis London: Minnesota University Press.

Robinson, T. 2020. “Digital video-based research in fashion: Visualizing affect and sartorial vitality.” International Journal of Fashion Studies 8 (1):105–120. doi: http://doi.org/10.1386/infs_00033_1.

Ruggerone, L. 2017. “The Feeling of Being Dressed: Affect Studies and the Clothed Body.” Fashion Theory: The Journal of Dress, Body & Culture 21 (5):573–593.

Stern, D. 2010. Forms of Vitality. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Todes, S. 2001. Body and World. Cambridge M.A.: Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Bibliography

Allen-Collinson, J., and J. Hockey. 2011. “Feeling the way: notes toward a haptic phenomenology of scuba diving and distance running.” International Review for the Sociology of Sport 46 (3):330–345.

Benjamin, W. 1999. The arcades project. Translated by Howard Eiland and Kevin McLaughlin. Cambridge, Mass.; London: Belknap Press.

Bolt, B. & Barrett, E. 2013. “Toward a ‘New Materialism’ Through the Arts.” In Carnal Knowledge: Towards a New Materialism Through the Arts, edited by B. & Barrett Bolt, E. London, New York: IB Taurus.

Candy, F., J. 2005a. “The Fabric of Society: an Investigation of the Emotional and Sensory Experience of Wearing Denim Clothing.” Sociological Research Online 10 (1).

Csikszentmihalyi, M. 1996. Creativity: flow and the psychology of discovery and invention. New York: HarperCollins Publishers.

Downey, G. 2005. Learning Capoeira: Lessons in Cunning from an Afro-Brazilian Art. Oxfort: Oxford University Press.

Eckert, C.M., and M.K. Stacey. 2001. “Designing in the Context of Fashion – Designing the Fashion Context.” Designing in Context: Proceedings of the 5th Design Thinking Research Symposium.

Entwistle, J. 1997. “Power Dressing and Fashioning of the Career Woman.” In Buy this Book: Studies in Advertisitng and Consumption, edited by Mica Nava, Andrew Blake, Iain MacRury, and Barry Richards. London: Routledge.

Entwistle, J. 2000. “Fashion and the fleshy body: Dress as embodied practice.” Fashion Theory: The Journal of Dress, Body & Culture 4 (3):323–347.

Entwistle, J. 2015. The Fashioned Body; Fashion, Dress and Modern Social Theory. 2nd ed. Cambridge, UK & Malden, USA: Polity.

Gallese, V. 2005. “Embodied simulation: From neurons to phenomenal experience.” Phenomenology and the cognitive sciences 4 (1):23–48.

Gaver, B., A. Dunne, and E. Pascenti. 1999. “Design: Cultural Probes.” Interactions 6 (1):21–29.

Grasseni, C. 2004. “Skilled visions: an apprenticeship in breeding aesthetics.” Social Anthropology 12 (1):41–55.

Hahn, T. 2006. Sensational Knowledge: Embodying Culture through Japanese Dance. Vol. 50. MIddletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press.

Leder, D. 1990. The Absent Body. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Marchant, S. 2011. “The Body and the Senses: Visual Methods, Videography and the Submarine Sensorium.” Body & Society 17 (1):53–72

Michael, M. 2012. “De-signing the object of sociology: toward an ‘idiotic’ methodology.” The Sociological Review 60:166–183.

Mulvey, L. 2009. Visual and other Pleasures. 2nd ed. Basingstoke [England]; New York McMillan.

Negrin, L. 2012a. “Aesthetics: Fashion and Aesthetics – a fraught relationship.” In Fashion and Art, edited by Adam Geczy and Vicky Karaminas, 43–54. London, UK: Berg.

Negrin, L. 2012b. “Fashion as an Embodied Art Form.” In Carnal Knowledge Towards a ‘New Materialism’ through the Arts, edited by Barbara Bolt and Estelle Barrett, London and New York. London and New York: I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd.

Negrin, L. 2016. “Maurice Merleau-Ponty: The Corporeal Experience of Fashion.” In Thinking Through Fashion: A guide to the key theorists, edited by A. Rocamora and A. Smelik. London, New York: I.B. Taurus.

Noland, C. 2008. “Introduction.” In Migrations of Gesture. Minneapolis London: Minnesota Universtity Press.

O’Connor, E. 2005. “ Embodied knowledge: The experience of meaning and the struggle towards proficiency in glass blowing.” Ethnography 1 (1):183–204.

Pink, S. 2007. “Walking with Video.” Visual Studies 22 (3):240–252

Pink, S. 2009. Doing sensory ethnography. London: Sage.

Robinson, T. 2019. “Attaining Poise: A Movement-based Lens Exploring Embodiment in Fashion.” Fashion Theory 23 (3):441–448.

Robinson, T. 2020. “Digital video-based research in fashion: Visualizing affect and sartorial vitality.” International Journal of Fashion Studies 8 (1):105–120. doi: http://doi.org/10.1386/infs_00033_1.

Robinson, T. 2023. “Body Styles: Redirecting Ethics and the Question of Embodied Empathy in Fashion Design.” Fashion Practice 15 (1):113–135.

Sinha, P. 2002. “Creativity in Fashion.” Journal of Textile and Apparel, Technology and Management 2 (4).

Spinney, J. 2006. “A place of sense: a kineasthetic ethnography of cyclists on Mont Ventoux.” Environment and Plannning D : Society and Place 24 (5):709–732.

Stern, D. 2010. Forms of Vitality. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sweetman, P. 2001. “Shop-Window Dummies? Fashion, the Body, and Emergent Socialities.” In Body Dressing, edited by Joanne Entwistle and Elizabeth Wilson, 59–77.Oxford: Berg.

Todes, S. 2001. Body and World. Cambridge M.A.: Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Wegenstein, B. 2006. Getting Under the Skin: The body in Media Theory. Cambridge, Massachusetts, London, England: MIT Press.

Woodward, S. 2007. Why women wear what they wear. Oxford, New York: Berg.

Young, I. 2005. On Female Body Experience. “Throwing Like a Girl” In On Female Body Experience. “Throwing Like a Girl” and Other Essays. New York: Oxford University Press.

Young, I.M. 1994. “Women Recovering Our Clothes.” In On Fashion edited by S. Benstock and S. Ferriss. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press.

This project would not be possible without the generous involvement of the following individuals who assisted and participated in this project:

Performer-participants: Bruno Panucci, Joy, Narmine Akketab, Zepp Hamilton

Video & sound editing and production: Jason Benedek

Videography: Gary Warner

Garment design and production: Todd Robinson & Nahum Mclean

The project was developed with the support of Doctoral research program and Fashion and textiles program, at University of Technology, Sydney.

I acknowledge the Gadigal People of the Eora and Boorooberongal People of the Dharug Nation upon whose ancestral lands this work was produced. I pay respect to the Elders both past and present, acknowledging them as the traditional custodians of knowledge for these lands.