VIDEO ARTICLE TRANSCRIPT

[Note: This is a transcript of a video article. Onscreen text appears left justified, while spoken words are indented. Individual elements from the transcript, such as metadata and reference lists, may appear more than once in the document, in order to be properly read and accessed by automated systems. The transcript can be used as a placeholder or reference when it is not possible to embed the actual video, which can be found by following the DOI.]

[0’30”]

§ 1 Purpose: What is performative beauty?

[Falk Heinrich]

This video article explores beautiful experiences that arise while engaging in physical activities, a dimension often overlooked in Western aesthetics. My goal is to critically re-evaluate and expand Western aesthetic theory by introducing the notion of performative beauty.

For my specific case study, I have selected Argentine tango, primarily because it is a somatic practice with which I am well-acquainted. My investigation is partially autoethnographic, rooted in my documented personal experiences.

[1’00”]

Footnote

There are numerous academic studies on Argentine tango investigating its genealogy, history, social, political, and (post)colonial significances, as well as its benefits in terms of physical and mental health, personal and social well-being, and interpersonal and intercultural communication, among other aspects. Additionally, there is a wealth of studies focusing on tango’s movement technique and aesthetics when viewed from the onlooker’s perspective. However, there is a noticeable gap in research when it comes to the aesthetic experiences of one’s own dancing. There is hardly any study on this particular subject matter.

[1’20”]

§ 2: Examples of beautiful experiences of dancing

[Falk Heinrich]

Argentine tango is an embraced couple dance; it is a social dance. People learn and dance it as a leisure activity.

There might be many reasons for wanting to learn Argentine tango. Surely, one of them is that it can be quite pleasurable in very distinct senses. The ingredients of this pleasure are, for example, listening and moving to tango music, sensing the partner’s body and energy, enjoying improvising, and engaging in a playful interaction with the dancing partner by rhythmically moving together with them as almost one entity. The concrete mixture of motives is very individual. Not everybody likes Argentine tango, but those who do get quite addicted to it and use immense amounts of time and resources to learn and master this dance in the hope of having many deeply satisfying and pleasurable experiences.

I remember having seen a video with interviews of old tango masters form Buenos Aires – so-called tangueros. One tanguero couple characterises the experience of tangoing as a kind of flying. In the video, he exclaims, ‘It’s beautiful; it’s beautiful’.

I have come across many descriptions of dancing as something beautiful that is highly appreciated by the dancer. But what does ‘it’s beautiful’ mean?

[3’05”]

§ 3 Thesis: A dancer has beautiful experiences when the tango is dancing the dancer

[Falk Heinrich]

In general, Western philosophical aesthetics has not considered the beauty of one’s own movements. I aim to propose a theory that expands the concept of beauty to include these experiences.

[3’30”]

Footnote:

Contrary, Chinese and Japanese philosophies ground aesthetics in the holistic experience of change and the extasy of no-self (Nishida, 1987).

[Falk Heinrich]

According to testimonies and my own experience, dancing is felt as beautiful when there is a flow of movements, but a kind of flow that heightens awareness. In these moments, dancing is effortless, which means that the dancers do not have to preconceive and intentionally execute movements. It rather feels as if the dancing itself is improvising with the dancer without them ever losing control of their steps. The dancers’ awareness is following the movements, and this awareness seems to guide their movements.

I begin with my thesis:

[4’15”, Falk Heinrich and onscreen]

Aesthetic experience of one’s own movements is possible when the dancer delegates their agency to the interaction proper. In these moments, it feels as if the dance and its interactions are dancing the dancer. One’s own movements are objectivised. This somatic experience is beautiful.

[4’40”]

§ 4 The question of academic validity

[Falk Heinrich]

A theory of beautiful experiences of one’s own movements raises the problem of academic validity. Since such a notion of the beautiful is deeply rooted in one’s own living body, it can, in principle, only claim validity for the one who is experiencing it. Only I can experience my movements; there is no common object all of us can observe. Thus, the experience of my own movements is not comparable to the experience of Van Gogh’s sunflowers or the statue of David by Michelangelo, which both present themselves as the same for all of us. That is why my investigation of performative beauty cannot be based on empirical data that somehow measure movement, its extension in space, its velocity, its acceleration.

Yet, everybody has a body, and most of us can experience and sense our own moving bodies. Furthermore, each of you watching the dancing in this video will neurologically re-enact or even simulate the observed tango movements. This allows you to scrutinise my assertions and listen to their echoes within yourself. And maybe you can recognise some of my assertions in your favourite activity, be it yoga, biking, hiking, tennis, making food or something else. The validity of my investigation and its findings lies in the recognition of my assertions within each of you and is thus purely subjective.

That said, the beautiful could never be measured and scientifically proven, only felt in pleasure. Beauty’s working can only hypothetically be explained. That is precisely what aesthetics tries to do, and that is what I try to do.

[7’00”]

Exercise 1: drawing a line

[Falk Heinrich]

Now, I want to invite you to perform a very simple exercise.

Start drawing a line – for example, a serpentine or waving line. Draw this line with your finger on the desk. Repeat this figure again and again. It does not matter whether the lines are perfectly aligned; the movement is important, not the resulting lines and patterns. Repeat and repeat.

Continue while I proceed with my elaborations.

[7’50”]

§ 5 Kinaesthetic awareness

[Falk Heinrich]

It is not easy to be aware of one’s own movement in the moment of moving. Any somatic sensibility seems to be seized by my perception of the space and its objects – for instance, the tactility of my dance partner or the tango music. We relate to the constituents of the world through purposeful intentionality. Our awareness is out there.

Normally, proprioceptive and kinetic awareness – that is, the registration of the angles, directions and dynamics of one’s limbs – is a background awareness that only takes prominence in moments of exhaustion or failure or, for example, when we learn new tango steps. At these moments, my awareness is directed at the usage of my body and on the evaluation of the rehearsed kinetic arrangement. This is called performative awareness. Typical questions in these situations include: What happens when I put my foot more to the left or dissociate my upper body more?

But rehearsing is, in most cases, not experienced as beautiful simply because the focus is on the intention to improve some shortfalls. Paradoxically, my will to dance well and beautifully seem to refute the possibility of beautiful experiences. To aesthetically experience one’s own dancing means that dancing must happen almost without will or intention. Yet, we all know that dancing depends on human agency, on our intentions; I must want my body to perform dance steps.

So, how can I dance without dancing? Expressed differently, how can I be danced while I initiate and execute dance movements? How can I aesthetically observe and experience myself dancing while I am ‘doing’ movements?

[10’25”]

§ 6 Aesthetic reflection: tango sculptures/stills

[Falk Heinrich]

Let me now clarify the notion of aesthetic reflection.

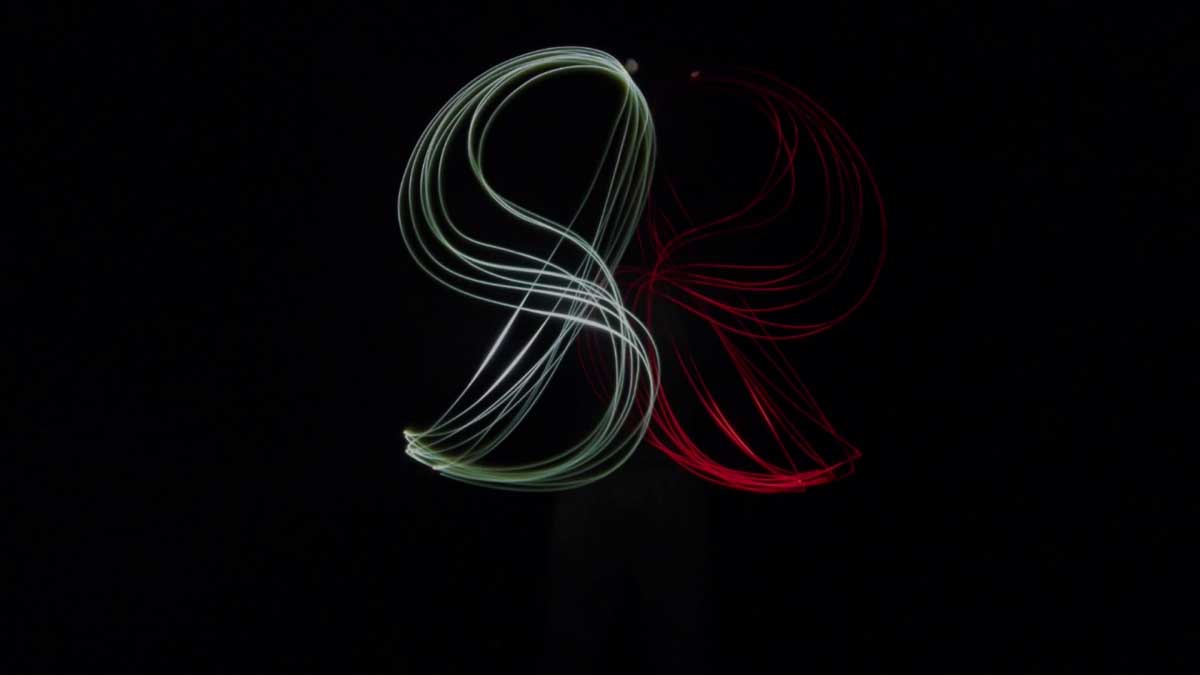

Immanuel Kant saw the pleasure of beauty as an outcome of a reflective judgment. Aesthetic reflection is based on purposelessness, which means that there is no immediate application of our perceptions in aesthetic situations. Aesthetic reflection is a free interplay of imagination and understanding. Kantian imagination and understanding are cognitive faculties or abilities. Imagination creates mental images by densifying the manifold of sense data into entities. In my video, the imagination transforms distinct frequencies of light into white and orange entities of a kind. But we also need Kantian conceptual understanding to support the perceptual creation of recognisable forms. Only the concept of a dancer lets us recognise the orange and white entities as human dancers.

Yet, the objective of aesthetic reflection is not primarily the recognition of recognisable forms, for example, of tango dancers. Aesthetic reflection purposelessly plays with this formational process by applying indeterminate concepts – concepts that are never finalised but are always incipient. The potential pleasure of contemplating images of tango dancers lies not in the identification of the depicted entities as specific dancers but rather in our imaginative play; the colours and forms; the energetic relationships between them; the possible narratives; and so on. According to Kant, aesthetic reflection is in itself pleasurable.

The philosopher Santayana says that aesthetic objects are objectifications of the sentiment of pleasure. Without such objectification, we could not possibly be aware of the beautiful. We need the perception of objects as canvas for our aesthetic pleasure.

Images of dancers are one thing; dancing is another thing entirely. So, how can I engage in the reflective awareness of my own movements while moving? How can I objectivise my own movements while dancing?

This is both a theoretical and a practical problem. The theoretical problem needs a comprehensive explanation. The practical problem requires a lot of exercise in somatic awareness.

[13’35”]

Exercise 2: drawing a line

[Falk Heinrich]

Let’s return to our little exercise. If you have stopped doing the serpentine line, please, take it up again. Draw the line on the table, again and again, the same line. Take some minutes. Then let the whole upper body be part of the movement. Let the drawing of the line move your shoulder. In time, you will get the feeling that the line is moving your body.

[14’30”]

§ 7: Awareness as another kind of objectivisation

[Falk Heinrich]

How should we understand a performative yet reflective kinaesthesia and proprioception? One thing is clear: here, reflection is not solely a cognitive occurrence that produces associations, thoughts or even arguments. Rather, it is the acknowledgement (or awareness) of performative and kinaesthetic possibility spaces. Let me explain: aesthetic reflection in action is tied to the practice of dancing. Reflection in action cannot be a contemplative interplay of imagination and understanding as the recurrent sensing of perceptual objects. The aesthetic interplay in action is embodied and performative. Kantian imagination becomes the kinaesthetic awareness of initiated actions. And Kantian understanding becomes performative in that it opens a space of possibility for further potential actions. Understanding is no longer based on representational concepts but on embodied movement patterns. These patterns can be sensed and realised by being varied in terms of energy, extension in space, rhythm, dramaturgy, etc. Now, understanding is prospective and draws on Kant’s notion of productive imagination.

But all this presupposes that proprioception and kinaesthesia, which are normally pre-reflective, become reflective (albeit not as mental representations). How does this happen?

[16’25”]

§ 8: Awareness in movement: practice

[Falk Heinrich]

The answer to this question is that something else takes over the agency to dance. How?

Tango is a codified dance that exists of a specific technique and a limited number of basic steps that can be infinitely varied and combined while dancing. Importantly, the steps and movements ‘afford’ interactions between the two partners. One step or movement opens a range of reaction possibilities for the partner. The initiated reaction affords a new range of movement possibilities and so on. Dancing tango is a continuous reaction cycle in which the dance partners react to each other – and the music. This can create a seamless flow of movements.

Let me show this with a concrete tango figure, the ocho adelante, or front ocho.

The premise of tango technique is that the hearts of the partners are always aligned with each other. This embodied relational technique allows for the transmission of impulses and the opening of spaces the follower can enter.

For example: if I, in the role of the leader, convey the impulse of a sidestep, my partner somatically senses this and makes the sidestep.

Now, I dissociate that is turn the upper body while the hips remain in front of my partner. The partner accepts the invitation, and she dissociates too, taking a step in front of me.

I follow her step to maintain the relationship.

I then dissociate to the other side. The partner accepts and follows into the empty space. Voila, a front ocho.

The important thing is that the action–reaction cycle implies a continuous role shift. The leader initiates by indicating an open space. The follower reacts and thus becomes, for a short while, the leader because the other must wait and follow the follower’s reaction.

This movement can be modified. For instance, a sacada can be incorporated. The leader steps into the space the standing leg of the follower occupies. She must now move her leg by taking up the leader’s energy. In these moments, the follower’s movement is not initiated by her, potentially causing a feeling of flying.

The important thing is that the interactional logic of tango yields moments in which my body, my soma, is reacting without my agency. This emerges even in very simple steps, such as this front ocho or even simple walking together (la caminada).

In these moments, I am free to let my somatical awareness follow and reflect our movements.

[19’40”]

Exercise 3: Drawing a line

[Falk Heinrich]

Let’s go back to our little exercise. Raise your moving hand, leave the table, and draw the same line vertically in the air, again and again. Maybe you want to follow my lines of light. Or maybe you imagine following the side contour of a body or any other serpentine-like object.

Don’t be creative; do not intentionally change the line. Just repeat and find pleasure in this line. Let the line engage the whole body. You may also use both your hands to draw two equal lines.

Maybe at some point in time, the movement feels automatic; the line draws itself downwards. Now, the line is moving your hand – maybe even your whole body. If not, be patient; let the music animate your movements.

Let your awareness follow the movements of your body. Your awareness is no longer occupied with drawing the line; the line is drawing itself. Feel the air around your hand. Feel your muscles working. Feel the weight of your arm and hand – all the while you draw the line in the air.

[21’10”]

§ 9 Awareness in movement: theory

[Falk Heinrich]

Evidently, someone must exert agency to get the interaction going. However, once the general tango movement patterns are embodied and sedimented as kinaesthetic memories, the interaction with my partner and with the music might take over. Then, one move affords the next.

Proponents of enactivism have proposed that interaction itself exerts agency and brings about participatory sense making due to perceptual crossing. Perceptual crossing is the reciprocal interplay of perceiving while being perceived, a shared point of perceiving each other while perceiving the same object. Moments of mutual perception experienced while dancing bring about an autopoiesis of interaction that now guides the dancers’ moves. Said differently, perceptual crossing distributes agency to the dance interaction.

In these (admittedly rare) moments of experienced flow, I do not intend to perform the movements; I experience that tango is dancing me. Now, I am free to perceive our dancing in aesthetic awareness.

Aesthetic awareness in action is not contemplative. Rather, it is an interplay of actuality and potentiality. It is not that I am actively looking for possible next steps. Aesthetic awareness in action observes by fashioning and adjusting my movement to my partner’s movements, to the rhythm and modus of the music and to the atmosphere of the place. Therefore, aesthetic awareness in action is retroactive because my somaesthetic awareness is the distributed agency of the interaction. The somatic awareness of one’s own movements yields the pleasure of the beautiful.

[23’35”]

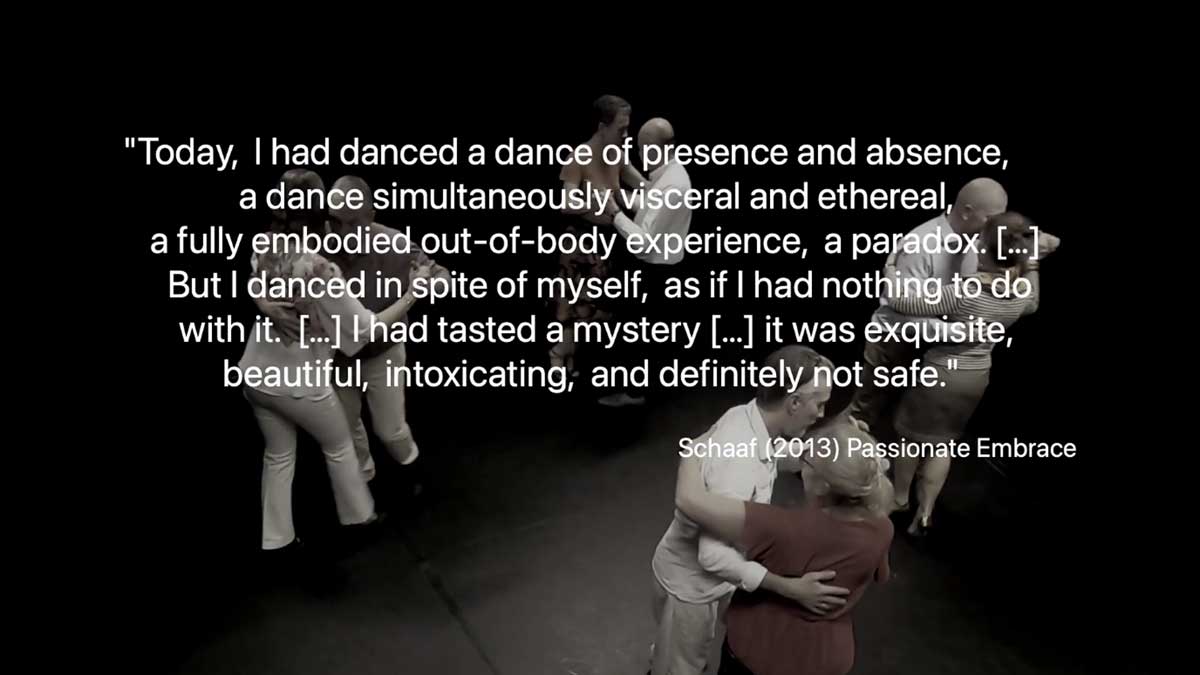

“Today, I had danced a dance of presence and absence, a dance simultaneously visceral and ethereal, a fully embodied out-of-body experience, a paradox. […] But I danced in spite of myself, as if I had nothing to do with it. […] I had tasted a mystery […] it was exquisite, beautiful, intoxicating, and definitely not safe.”

Schaaf (2013) Passionate Embrace

[24’00”]

§ 10: Application to other fields

[Falk Heinrich]

In principle, my notion of beauty is applicable to all somatic activities, not only to the various forms of social dancing from Viennese waltz to lambada. Performative beauty also extends to everyday aesthetics, such as yoga, tai chi, skiing, mountain biking, or even preparing a meal.

Evidently, performative beauty is also contingent on the attitude and skill of the practitioner. For a yoga novice, the postures are challenging, requiring focused energy and volition to achieve correct body arrangement. However, with repeated practice, awareness becomes liberated, allowing it to flow within and around the practitioner. This may lead to an enhanced awareness of the entire body seamlessly integrated with the surroundings.

When you know how to ski in deep snow, the slope and the snow support you in hovering from bend to bend; your somatic awareness merely follows your movements.

Performative beauty can be experienced with all kinds of movement and actions, even while cutting onions. Chefs can slice vegetables without initiating every single cut. It is as if the vegetable dictates the slicing.

It is like in our little exercise: the line draws your movements. The experience of the movement might be beautiful and not the line.

[Credits, 25’48”]

Idea, video, text: Falk Heinrich

Dancers:

Per Andreasen, Birgitte Findinge, Falk Heinrich, Runa T. Hellwig, Nellie Cassandra Maargaard, Peter Nielsen, Susanne Mølgaard Skeem, Poul Skeem.

References:

Heinrich, F. (2023). A Somaesthetics of Performative Beauty – Tangoing Desire and Nostalgia. Routledge.

Kant, I. (2000). The Critique of Judgement. Cambridge University Press.

Nishita, K. (1987). An Explanation of Beauty. Monumenta Nipponica, 42(2).

Santayana, G. (1955). The Sense of Beauty. Dover Publications.

Schaaf, S. (2013). Passionate Embrace – Faith, Flesh, Tango. Clements Publishing Group.

Music:

Fresedo, O. Canto de amor; La clavada; Recuerdos de Bohemia

Mozart, W. French Nursery

Piazolla, A. Milonga del Angel (int. Kuschnerova, E.)

La Tabu. Ocho Octubre; Que?

Selected literature in Argentine Tango:

Anzaldi, F. B. (2012). Politischer Tango. transcript Verlag.

Baim, J. (2007). Tango—Creation of a Cultural Icon. Indiana University Press.

Chasteen, J. C. (2004). National rhythms, African roots: The deep history of Latin American popular dance. University of New Mexico Press.

De Spain, K. (2003). The Cutting Edge of Awareness. In Taken by Surprise. Wesleyan University Press.

Foster, S. L. (2003). Taken by Surpise. In Taken by Surprise. Wesleyan University Press.

Haller, M. (2014). Abstimmung in Bewegung. transcript Verlag.

Manning, E. (2009). Relationscapes—Movement, Art, Philosophy. MIT Press.

Savigliano, M. E. (1995). Tango and the Political Economy of Passion. Westview Press.

Thompson, R. F. (2005). Tango: The art history of love. Vintage Books.

Thanks to Aalborg University, Tango Aalborg, my tango teachers and dance partners.

References

Heinrich, F. (2023). A Somaesthetics of Performative Beauty – Tangoing Desire and Nostalgia. Routledge.

Kant, I. (2000). The Critique of Judgement. Cambridge University Press.

Nishita, K. (1987). An Explanation of Beauty. Monumenta Nipponica, 42(2).

Santayana, G. (1955). The Sense of Beauty. Dover Publications.

Schaaf, S. (2013). Passionate Embrace – Faith, Flesh, Tango. Clements Publishing Group.

Music

Fresedo, O. Canto de amor; La clavada; Recuerdos de Bohemia

Mozart, W. French Nursery

Piazolla, A. Milonga del Angel (int. Kuschnerova, E.)

La Tabu. Ocho Octubre; Que?

Selected literature in Argentine Tango

Anzaldi, F. B. (2012). Politischer Tango. transcript Verlag.

Baim, J. (2007). Tango—Creation of a Cultural Icon. Indiana University Press.

Chasteen, J. C. (2004). National rhythms, African roots: The deep history of Latin American popular dance. University of New Mexico Press.

De Spain, K. (2003). The Cutting Edge of Awareness. In Taken by Surprise. Wesleyan University Press.

Foster, S. L. (2003). Taken by Surpise. In Taken by Surprise. Wesleyan University Press.

Haller, M. (2014). Abstimmung in Bewegung. transcript Verlag.

Manning, E. (2009). Relationscapes—Movement, Art, Philosophy. MIT Press.

Savigliano, M. E. (1995). Tango and the Political Economy of Passion. Westview Press.

Thompson, R. F. (2005). Tango: The art history of love. Vintage Books.